If writing is going to happen, it might begin after my first cup of coffee. I achieve this by pouring dark House beans into the grinder and roaring this until I get a fine powder, dumping it into a paper-lined funnel, pouring in cold water, and flipping on the switch. While I wait for this to brew, I pour water into my Keurig for two cups–to share with my husband. I toss in a House K -cup and press “ON.” The two pots come together and finish together. I take my cup of Keurig and fill it up from the regular pot. Then I slide into my Lazy-Boy, switch on my cup heater, and set the cup of alertness down. I turn on the laptop, wait for warmup, and take my first sip. I know it will take more than this to get all of my lights to start blinking.

I’m usually running empty when I wake. Very few logical thoughts–only intuitive-actions can get me this far in the morning. Family knows not to talk too loudly or, if possible, not at all, “Let me have my first cup of coffee,” before I’m expected to make some decision or sign some legal document. If I were to exaggerate this, I’d be funny. I’m speaking the truth. It will take that first cup of caffeine to trigger the neurons in my gray matter before I get the eye-opening, thought-focusing jolt to begin my day and clog up that great big cavity of nothingness. On a good day, I might start typing, officially brainstorming about and writing on my next project, which is now my latest novel, the third in a series, Where Two Rivers Meet.

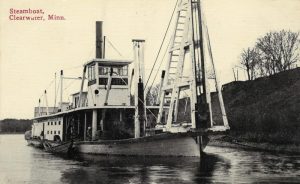

But sometimes, I need more than java. I need physical inspiration–whether I am trying to fill in a plot segment, follow the yearning of a poem, or conceptualize a blog, without which I am just a blinking cursor. I feel like the chocolate Easter eggs or bunnies, hollow inside. So on one of my good days, I joined my sister on a trip to the Mississippi River, to wander on the path my protagonist, Abigail, would have walked when she disembarked the steamboat Governor Ramsey below the bluffs at Clearwater.

The date was August something, 1855. She would become the first white woman to come to the village, and she would work as the townsite’s hotel housekeeper. Brave she must have been to come alone from Vermont, via, stagecoach, train, and steamboat to an area wild with male ambition. Her brother-in-law, Dr. Jared Wheelock, the first doctor in Wright County, Minnesota, would be there to keep her company and in the area to keep an eye on her. Her cousin’s husband would be building a bigger and better hotel eventually, but it would be a couple of months before Jared’s wife, Abigail’s sister, would join her in the town. Yet, all this I know and have written about already. While I love the free feeling of nature down here–birds singing and light breezes moving the trees and the river’s current, I need something worthy of writing.

As I turned around, a tree with two huge cavities lured me to come closer–to gaze into its hollowness, touch its rough bark, feel its smooth green leaves, and look UP. Thick branches, wide and round spread their leaves above and over our path, joining other branches and other greenness, forming canopies of sorts. However, the tree alongside this enchanted forest-like walkway beckoned me into imagining life before I arrived on the scene, before Abigail arrived, and before white male settlers staked their claim to this part of the Mississippi River. So beguiled about this tree, I searched the Internet for answers. “A tree hollow or tree hole is a semi-enclosed cavity which has naturally formed in the trunk or branch of a tree. They are found mainly in old trees, whether living or not. Hollows form in many species of trees, and are a prominent feature of natural forests and woodlands, and act as a resource or habitat for a number of vertebrate and invertebrate animals.[1]”

Read on in Wikipedia to learn that “it may take 220 years for hollows suitable for larger species to form.” So how long has this tree been standing? Would Abigail have seen it in its youthful stage? Had it already developed a small hole? The article provided more. I learned that this hole is never truly empty. Yes, all sorts of creatures may live or burrow inside.

All writers have the block one way or another. Mark Twain, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, and others. They give great advice on 13 Famous Writers on Overcoming Writer’s Block. For now, I believe in myself again. I am inspired and feel my synapses firing again.